Manuscripts, typescripts, notebooks, correspondence and drafts… The reading of “The David Lodge Papers”[1] enables a better understanding of the British writer’s work, while offering insights into his creative process and method. Indeed, “[w]hatever autonomy and internal logic formal analysis may reveal in a work of art, the actual work is only one among its multiple possibilities… The work now stands out against a background, and a series, of potentialities. Genetic criticism is contemporaneous with an aesthetic of the possible.”[2]

This, is also true of a whole literary work. Delving into the typescript of “The Devil, the World and the Flesh” (written when David Lodge was only 18 years old, between 1952 and 1953 – a first unpublished novel which is not made available to researchers without written authority from the author), highlights how it carried the germs of many characteristics which have become specific to Lodge’s style and themes… to his “small world.”

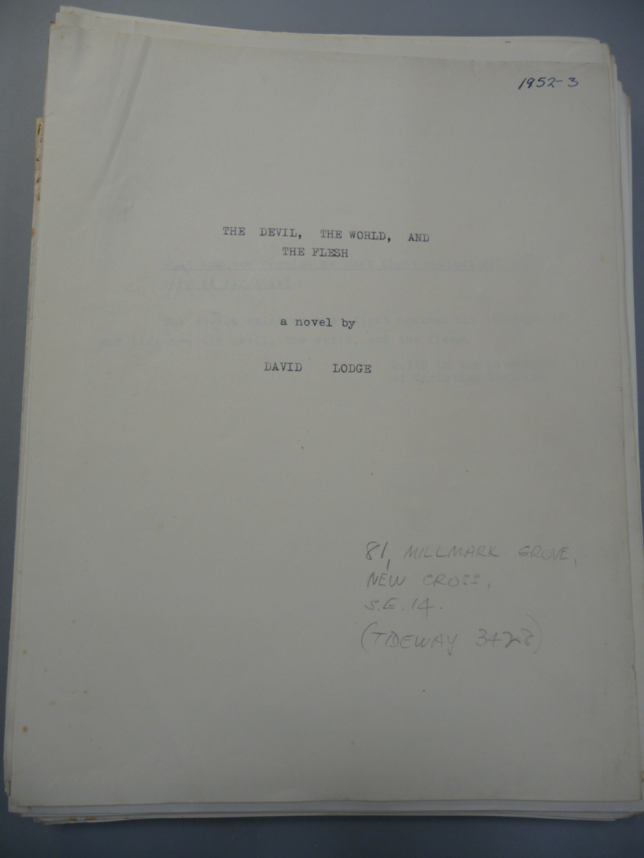

The Devil, the World and the Flesh

Typescript’s cover

With permission of the author and Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections,

University of Birmingham

This typescript (composed of 326 pages) is all that is left from the writer’s first “youth novel.” The few words, hand-written with a black pencil, on the first page give information on the years he wrote it as well as the address where he used to live at the time: “81, Millmark Grove, New Cross,” situated in Brockley, London, is a place that will become part of many other of his novels’ setting)

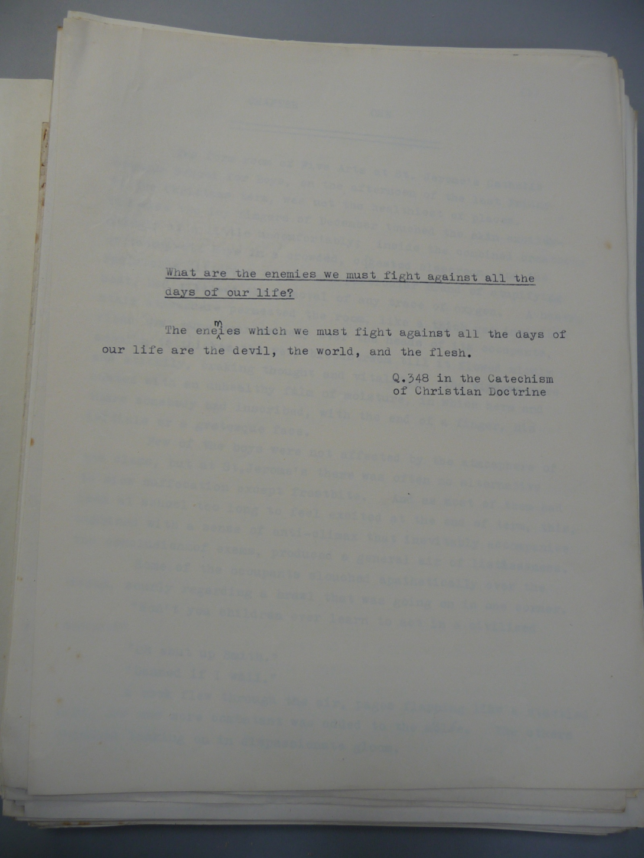

The title refers to question 348 of Catechism: “Which are the enemies we must fight against all the days of our life? The enemies we must fight against all the days of our life are de devil, the world and the flesh.”

The Devil, the World and the Flesh

Typescript’s epigraph

With permission of the author and Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections,

University of Birmingham

The writer was quite embarrassed by this very first novel as he explained in the first volume of his Memoir published in 2015: “I preserved the typescript and read it, or rather skimmed through it, when writing this book, frequently cringing with embarrassment at the naivety of my eighteen-year-old self.” (Lodge, Quite A Good Time To Be Born, p. 166)

Yet, it is really striking to discover how this novel contains many traits that will become characteristic of the writer’s themes: academic education, Catholicism, sexual desire vs. moral dilemmas; and, of course, the art of writing about characterization and settings, literary references as well as a very vivid, visual representation of a fictional world. The plot was described by Lodge in the foreword of his first published novel, The Picturegoers (1962):

“The hero, a priggish and introspective Catholic schoolboy, is attracted to the sexy daughter of the history master at his Catholic grammar school, and gets her pregnant, causing great scandal in school and parish. In the denouement the girl dies in childbirth, heroically refusing a therapeutic abortion, and absolves the hero from guilt by confessing that she deliberately seduced him, leaving him to be consoled by her more high-minded sister, who has recently returned home after trying her vocation as a nun. This latter character was obviously the prototype of Clare in The Picturegoers. The setting of the earlier novel, called ‘Bricksham’, is essentially the same as the ‘Brickley’ of the later one, and both were based on the part of south-east London in which I grew up myself, Brockley and New Cross. I returned to it in Paradise News” (xii)

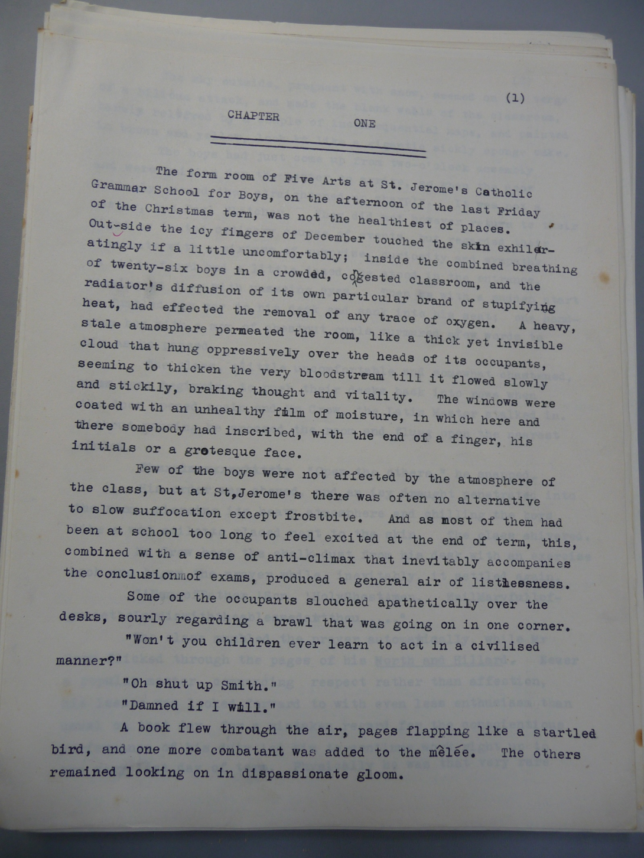

The incipit of the novel reminds the reader of the numerous realistic descriptions, in media res, of students attending courses at University, for instance, Lodge will write on, many years later in Nice Work (1988) or Small World (1984):

“The form room of five arts at St Jerome’s Catholic Grammar School for Boys, on the afternoon of the last Friday of the Christmas term, was not the healthiest of places. Outside, the icy fingers of December touched the skin exhilaratingly if a little uncomfortably; inside, the combined breathing of twenty-six boys in a crowded, congested classroom and the radiator’s diffusion of its own particular brand of stupefying heat, had effected the removal of any trace of oxygen (…) The windows were coated with an unhealthy film of moisture in which here and there somebody had inscribed with the end of a finger, his initials or a grotesque face.” (Typescript, p. 1)

The Devil, the World and the Flesh

Typescript, p. 1

With permission of the author and Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections,

University of Birmingham

Lodge has alluded to his literary influences and particularly that of James Joyce while writing this novel: “The hero, Paul Fletcher (…) is bookish, self-obsessed, nourishing literary ambitions, desiring sexual experience but restrained by his religious beliefs – in other words a self-portrait modelled on the adolescent Stephen Dedalus.” (Lodge, Quite A Good Time To Be Born, p. 167) And indeed, from then onwards, Joyce has been a model for the writer – committed to language at work,mixing up realism and fiction, humor and seriousness, literature and criticism.

He has always favored a self-reflexive genre, both critical and self-conscious towards its own mode of being, giving information to the reader as well as a reflection on the relationship between fiction and reality. And his work abounds with allusions, structural innovations and witty incarnations of literary theory in the lives of his characters – offering entertainment for all those willing to thread their way between puns and intertextual references. According to him, this technique is strongly rooted in the discovery of Ulysses: a novel with a prose “combining humour, religious allusion, archaisms, colloquialisms, scientific terminology and mimetic syntax (…) endow[ing] the familiar with the shock of the new.” (Lodge, Quite A Good Time To Be Born, p. 195) He added, a few pages later:

“As well as evoking the physical and mental life of [the] personages with unprecedented fine-grained realism, he shows them to us in the course of the book through the distorting lens of various specialised and artificial kinds of discourse – newspaper journalism, literary parody, surrealism, catechism, cheap romantic fiction for women, and several others – so that the novel is as much about its own medium, language, as about the world […] From that time onwards he was my literary hero.” (p. 197)

The term distorting lens is interesting as it perfectly illustrates how writing and seeing are intertwined in Lodge’s work and how the use of visual devices – whether textual anamorphisms, cinematic or theatrical references – is characteristic of his style; reflecting how the art of writing is, according to him, an art of persuasion: “effects achieved in order to persuade the reader to view experience in a certain way.” (Lodge, The Novelist at the Crossroads, p. 59)

A lexical field linked to sight and which seems to frame, literally, some of the scenes depicted by the narrator, therefore invades the text. On page 3 of the typescript, the protagonist comes back to school after the death of his girlfriend and describes the scene as follows:

“Paul, still sitting as if in trance, looked around the class. The events of the last few days had damaged the hairspring balance of his emotions, and he seemed to see his classmates as if they were in another world to himself. ‘En masse,’ they all looked quite alike: just row after row of familiar corpses, with their pimply suet-pudding faces. Yet, each had his own intense individuality: Smith, sharp, tiny, eager to please; Cripps, a great hulk of a fellow, gazing stupidly at the master, his anthropoid jaw sagging; his own friend, Lawrence Elton of the Chestnut curls, gracefully draped over a dangerously tilted chair; or Skate, who has dropped Latin, reading the news of the world under his desk. Did he really belong to the same world as these? Was he here at all?”

Besides, this synoptic view announces the descriptions Lodge will make of his various characters attending mass, one by one, in How Far Can you Go? (1980), though the latter will be much funnier, and the dilemmas they will also face – as often in Lodge’s novels – in order to reconcile sexual attraction to religious faith.

Theatrical references are also scattered throughout the text. Echoing the “Dramatise! Dramatise!” to which Henry James (an author he would write on, years later) exhorted himself. On page 207, for instance:

“All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players, might be true, but life wasn’t a play. It was a good tragedy when you knew that the death was coming at the end, when the whole drama had been concerned with building up to, and preparing the audience for the final catastrophe. But even Aristotle couldn’t formularize life. You were walking along happily after your exams, whistling ‘I’m dreaming of a White Christmas’ when suddenly someone came up and told you that the girl you were in love with was going to die. Just like that. It would have been booed off the stage. But it had happened.”

Besides, Lodge’s desire to become a writer can be felt, already, between the lines: “He began to talk of things never hitherto shared with anyone; his ambitions to be a writer, his theories on style, his immature philosophy.”

On page 10, after the narrator has just resisted Ruth’s advances, he evokes the writers that Lodge admires: “After all, the experience. And he wanted to be a writer, didn’t he? Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, – how did they get their experience – and they were Catholics, weren’t they? A mortal sin. But was it?”

Lodge was often described as a “Catholic writer.” Throughout his work, the question of faith has indeed been at stake and this can be strongly felt in this early novel; even if a gradual waning of orthodox religious belief in the implied author, can be traced in his latest novels such as Therapy (1995) or Deaf Sentence (2008).

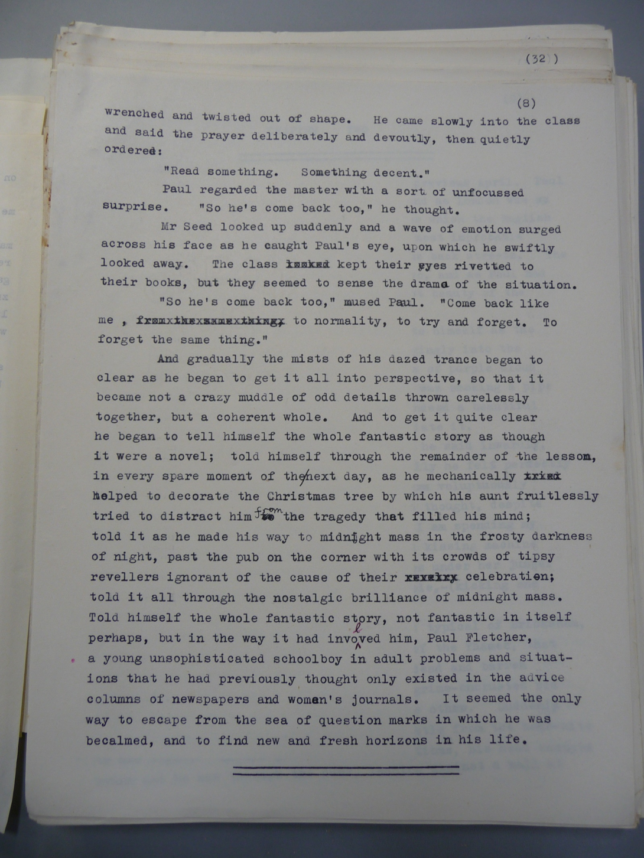

Skimming through the manuscript of The Devil, The World and The Flesh allows to see how it carries the germs of many characteristics of Lodge’s writing. It therefore helps to get his all work into a new perspective, close to the one offered by the protagonist, Paul Fletcher: “[h]e began to get it all into perspective […] And to get it quite clear he began to tell himself the whole fantastic story as though it were a novel […] not fantastic in itself perhaps, but in the way it had involved him…” (p. 8)

The Devil, the World and the Flesh

Typescript, p. 8

With permission of the author and Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections,

University of Birmingham

Genetic criticism has the power to trace, from ancient labors of writing, the arts of world making that a writer’s creative imagination is capable of. And indeed, making worlds, is an image often used by Lodge when dealing with literary creation: “To write a novel is to fill a hole that nobody, including oneself, was aware of until the book came into existence. First there was nothing there; then, a year or two (or three) later, there is something – a book, a whole little world of imagined people and their interlocking fortunes.” (“Why Do I Write?”, in Write On, p. 77.)

Throughout this typescript, one can witness and explore how these “possible worlds,” have always been part of the author’s imagination. Genetic criticism also underlines the importance of the roots of a whole work of art, this specific reading turning itself into the exploration of an “aesthetic of the possible,” as well as a reconstruction of the compositional history of a writer’s stories.

Thus, we can’t help viewing the drawing which can be found in the papers related to the novel Small World (evoking both the pins that are attached onto researchers’ chests during conferences – giving details about them – and that of an earth globe), as a vivid image both illustrating and duplicating David Lodge’s “small world…”

Drawing

With permission of the author and Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections,

University of Birmingham

[1] The David Lodge Papers, Box 25, 326. This typescript is held at the Cadbury Research Library (“Special Collections Department,” University of Birmingham.)

[2]. M. Contat, D. Hollier, J. Neefs (eds.), Yale French Studies 89, “Drafts,” 1996.